Symmetric faces are attractive

Symmetry is one aspect of faces that has been extensively studied by many researchers in relation to attractiveness. The most common method used to investigate the effect symmetry has on the attractiveness of faces involves manipulating the symmetry of face images using sophisticated computer graphic methods and assessing the effect that this manipulation has on perceptions of the attractiveness of the faces. Typically, perfectly symmetric versions of a set of face images are manufactured and presented to subjects along with the original (i.e. relatively asymmetric versions). Participants are then asked to indicate which face is more attractive, choosing between a perfectly symmetric version of a given face and the original version. Because the faces used in these tests differ in symmetry but not in other facial characteristics, these findings demonstrate that symmetry is a visual cue for attractiveness judgements of faces. Although studies have generally shown that people prefer symmetric versions of faces to the original (i.e. relatively asymmetric) versions, there has been considerable debate about why people prefer symmetric faces.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symmetric Female Face | Original Female Face | Asymmetric Female Face | Symmetric Male Face | Original Male Face | Asymmetric Male Face |

|---|

Explanations of the attractiveness of symmetric faces

Two different explanations have been put forward by researchers to explain attraction to symmetric faces: the Evolutionary Advantage view (which proposes that symmetric individuals are attractive because they are particularly healthy) and the Perceptual Bias view (which proposes that symmetric individuals are attractive because the human visual system can process symmetric stimuli of any kind more easily than it can process asymmetric stimuli).

The Evolutionary Advantage view proposes that symmetric faces are attractive because symmetry indicates how healthy an individual is: while our genes are such that we are designed to develop symmetrically, disease and infections during physical development cause small imperfections (i.e. asymmetries). Thus, only individuals who are able to withstand infections (i.e. those with strong immune systems) are successful in developing symmetric physical traits. Indeed, some (but not all) findings from studies of health in humans and many animal species have observed such a relationship between symmetry and indicators of health, with healthier individuals being more symmetric. For example, swallows and peacocks with symmetric tail feathers are particularly healthy and preferred by potential mates. Under the Evolutionary Advantage view of symmetry preferences, symmetric individuals are considered attractive because we have evolved to prefer healthy potential mates.

While the Evolutionary Advantage view suggests that attraction to symmetric individuals reflects attraction to healthy individuals who would be good mates (i.e. will have healthy offspring), the Perceptual Bias view of symmetry preferences makes a very different claim. Our visual system may be ‘hard wired’ in such a way that it is easier to process symmetric stimuli than it is to process asymmetric stimuli. Because of this greater ease of processing symmetric stimuli, symmetric stimuli of any kind might be preferred to relatively asymmetric stimuli. Under the perceptual bias view, preferences for symmetric faces are no different to preferences for symmetric objects of any kind. Indeed, it has been shown that people prefer symmetric pieces of abstract art and sculpture to relatively asymmetric versions.

Testing the Evolutionary Advantage and Perceptual Bias accounts of symmetry preferences

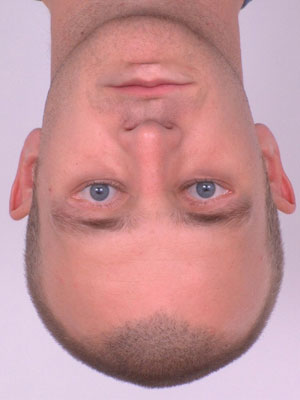

|

| Face processing is disrupted when faces are inverted. This face looks normal when inverted, but click on the face to see what it really looks like. |

|---|

Little and Jones (2003) carried out a study that investigated why people prefer symmetric faces to asymmetric faces, testing predictions derived from both the Evolutionary Advantage view and the Perceptual Bias view of symmetry preferences. Previous studies have found that symmetry had a bigger effect on the attractiveness of opposite-sex faces than own-sex faces and have suggested this is because opposite-sex faces are an example of ‘mate choice relevant stimuli’ (i.e. they are the faces of potential mates and own-sex faces are not).

Little and Jones noted that it is well established that inverting face images (i.e. turning them upside down) reduces the ease with which they can be processed and are perceived as being people. While people find it easy to process faces that are the right way up, face processing is disrupted by inversion to a far greater extent than processing of other types of visual stimuli is. Furthermore, inverted faces are processed more like other objects when inverted than when they are upright. Inverting faces, however, will obviously not alter how symmetric the faces are. So while opposite-sex upright faces are ‘mate choice relevant stimuli’ (i.e. are easily perceived as potential mates) inverted faces will be perceived more like objects, even though both inverted and upright faces will be equally symmetric. While the evolutionary advantage view suggests that preferences for symmetric faces will be weaker when the faces are inverted (because they will be perceived as less mate choice relevant), the perceptual bias view suggests that inversion will have no effect on symmetry preferences because symmetry is attractive in any type of stimulus. With this in mind, Little and Jones tested if inverting the faces used to assess preferences for symmetric faces weakens the strength of symmetry preferences (which would support an Evolutionary Advantage account of symmetry preferences) or if symmetry is equally attractive in upright and inverted faces (which would support a Perceptual Bias account of symmetry preferences).

Little and Jones found that symmetric faces were judged more attractive than asymmetric faces when faces were shown the right way up, but not when the faces presented were inverted. Because this suggests that symmetry is more attractive in mate choice relevant stimuli than in other types of stimuli, Little and Jones' findings support an evolutionary advantage account of why symmetric faces are attractive and present difficulties for the Perceptual Bias account (which proposes that symmetry will be preferred in stimuli of any kind).

Suggested further reading

- (168 kB) (2003). Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 270: 1759-1763.